One of the fantastic rewards of performing research on a specific period in history or genre of literature is that, from time to time, you almost always stumble upon, by sheer accident, a quaint and not-so-well-known story that not many folks are aware of. This story is one of those gems.

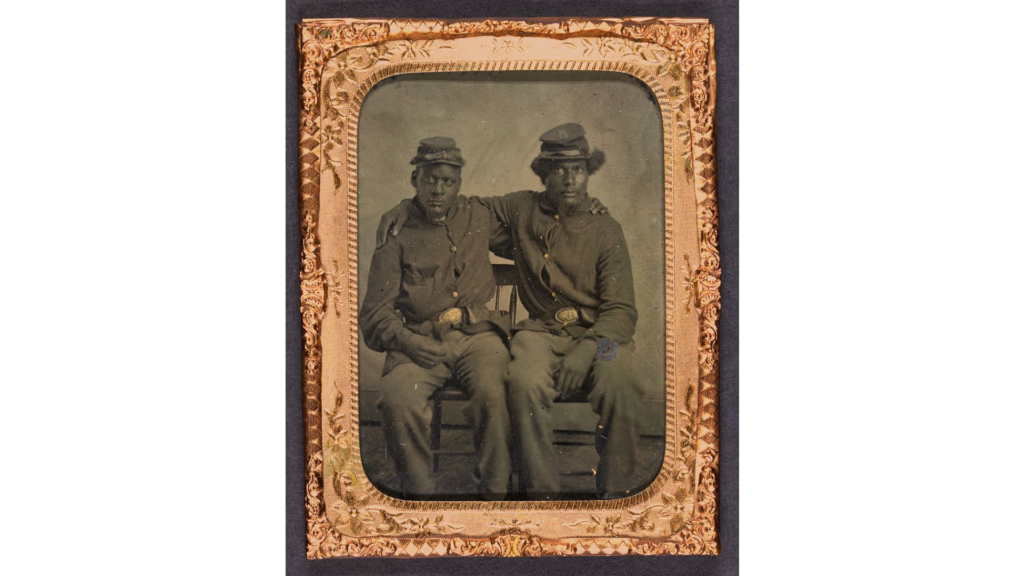

By the end of the Civil War, there were over 179,000 blacks serving in Union ranks; another 19,000 served in the Navy. Over 40,000 blacks lost their lives to extinguish slavery and preserve the Union. However, in the infancy of the war, Union recruiters turned down free black northerners for the cause; after careful consideration and examination on this matter, President Lincoln arrived at the decision to ‘muster’ black soldiers and permit them to serve. Despite their heroism and acts of bravery equaled to that of white soldiers, black soldiers were treated harshly and cold. They were paid less money; they could not advance in Union ranks or become commissioned officers. If they were captured during battle, they could immediately be returned to a state of slavery or even executed. All these dangers, however, did not stop John Mitchell from enlisting. But his enthusiasm was walking a thin line, and it broke; Private Mitchell became disenchanted with the cause he had believed in; his treatment by white officers was cruel and unusual. In several instances, he was even shackled for scuffles with other men by white officers. Disillusioned to serve with his regiment any further, Private Mitchell put in a requisition for a transfer; not caring where a conveyance would transport him to, he said, “I was willing to go into any other company in the regiment.” His request was evaded. He continued to endure abuse and physical confrontations with his fellow white officers. Finally, on November 22nd, 1863, Private Mitchell deserted his post that he was stationed at in Millikin’s Bend, Louisiana. (I propose the contention that Private Mitchell was not deserting his freedom promised by military service; on the contrary, he constructed his own technique to establish freedom for himself and others like him who were subjected to abuse and indignation in the Union Army.)

Desertion was a major problem in the Union Army. Soldiers went without clothing, the food was tasteless and scarce, soldiers were not adequately trained to handle the horrors of the battlefield that awaited them, and many found themselves in self-pity and swelling with homesickness. (It sounds cheesy, but many of the Union Soldiers were young and had never been far away from home and found it difficult to deal with.) The search for Private Mitchell was an arduous five months; finally, on April 15th, 1864, Private Mitchell was captured by Captain William Hubbard. He took Mitchell into custody and had him transferred to Vicksburg, Mississippi, where he awaited his court martial trial.

On June the 15th of 1864, Private Mitchell was tried and convicted of desertion of the United States Army. No black person could serve on a military court; it was only reserved for commissioned white officers. Despite his confession of horrible abuse and neglect and his impetuous desire to transfer, the white officers ignored his entire testimony. The officers sentenced Mitchell to four months of hard labor with him being shackled to a 12 pound iron ball for the entire duration. While the court martial for desertion could have merited the punishment of death, the white officers reprimanded instead of executing. However, the story does not end here.

Shortly after the trial, one General John Hawkins got word of this particular case and reviewed it for his own personal curiosity; as it turns out, General Hawkins was immensely dissatisfied with the verdict imposed on Private Mitchell. He decided to take the matter into his own hands. Reflecting on the case heavily, General Hawkins opined that Private Mitchell showed ‘his desertion was premeditated’; consequently, Mitchell was not entitled to any leniency. Since desertion was so common among Union Soldiers, and that Private Mitchell was a black soldier under white command, he decided to make an example out of Private Mitchell. General Hawkins ‘altered’ the final sentence. Private Mitchell was to face a firing squad for his desertion of the United States Military. It is to be discussed and appreciated that the same army that promised Private Mitchell his freedom, was now administering a death sentence on him. On September 15th, 1864, Private John Mitchell was executed for desertion by a firing squad.

So, what of this case? First off, I am not castigating the United States Military or its actions. What I am attempting to demonstrate is a valuable history lesson of the time. Race and color were unbreakable barriers in Private Mitchell’s time. This essay, I hope, captures how serious and incomprehensible it was for black men to even be acknowledged for fighting for a country that did not even recognize them as citizens, which they were not. If racism and division still exist in this country (which they do), this essay, I would hope, serves as a brutal reminder of how far violence will take us and how necessary it must be for our nation to extinguish our physical observation of one another. Private Mitchell, for most of his life, did this alone.

© 2024, Mark Grago. All rights reserved.