The most incomprehensible part of this question is the least undermined. The English language has provided more versions of the Bible that most other languages can boast of; we should take great pride in ALL the ‘English’ translations we have; however, that is not the case; in fact, we are more divided on this issue than ever before! We simply do not appreciate our beautiful language (and the sacrifices that have been made to create our translations).

Subsequently, I am in FULL denial that there is such a statement as the best version; to demonstrate this on a more professional paradigm, I would think of a version that ‘appropriately’ fits the job. For instance:

Witnessing or new coverts? (New Living Translation)

Detailed, word-for-word study? (English Standard Version, New American Standard, NIV)

Public reading? (NIV, New Revised Standard Version-my personal favorite)

Children: (New International Reader’s Version, Today’s English Version)

Adults with reading disabilities? (New International Reader’s)

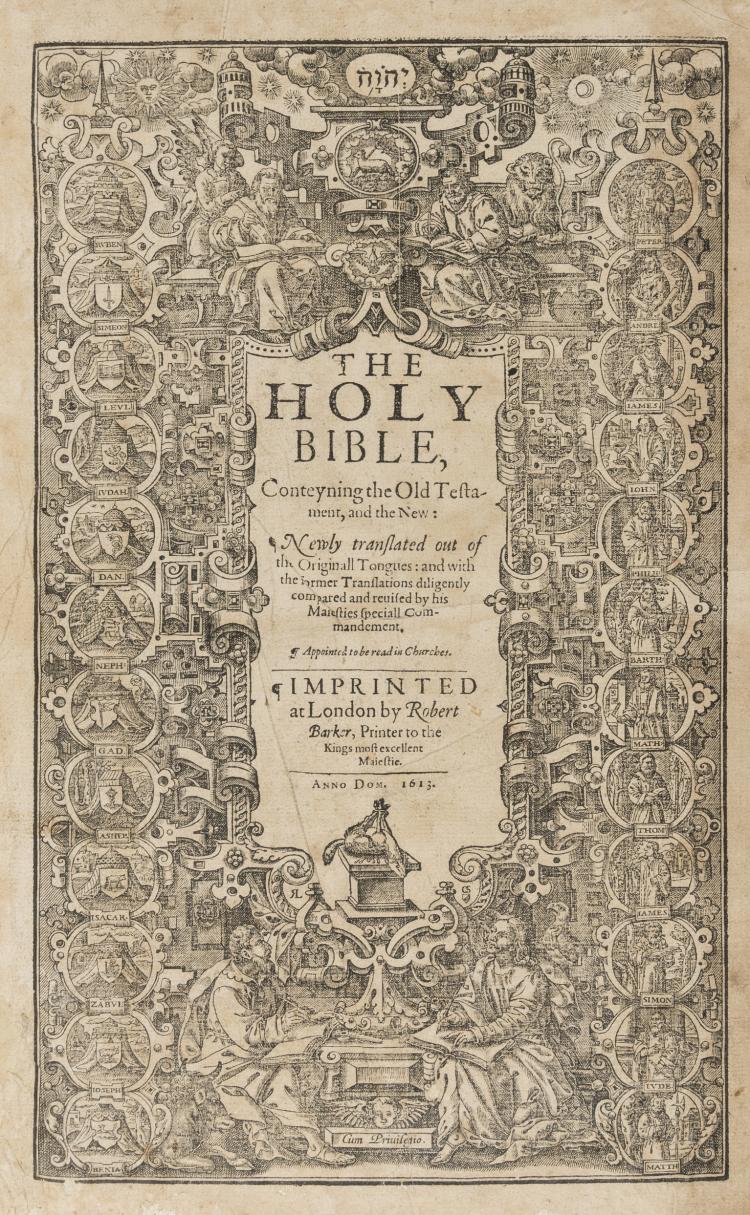

Weddings, funerals, special occasions? (King James Version, 1599 Geneva Bible. This was the FIRST English Bible to arrive on the shores of America, not the King James!)

Memorizing scripture? (NIV)

While this is ALL just my opinion, it should be noted that Christians should pick a Bible for the correct task at hand! That is the point I’m attempting to make! You must cast your biases aside in favor of advantageous and simplistic results. In other words, you may be falling short in getting your point across simply because of the ‘language’ you are using to get your ‘failed’ point represented. (A person who is COMPLETELY unfamiliar with the doctrines of the Bible is not going to understand your intentions if you are using a 1611 King James Bible to explain it to them! They’re just not! I know that is difficult for some of you to swallow!)

Permit my contention a bit further.

Formal Equivalent vs. Dynamic Equivalence

According to scholars, translations generally fall into two extremes. On the left side(I don’t mean politically)is the group of translations that attempt a word-for-word meaning of the verses. If the Greek passage has five words, the English version will attempt the same (in translation)as five words; this approach attempts to give accurate representation to the Greek and Hebrew syntax(the arrangement of words in a sentence), to reduce the vocabulary to its PUREST meaning. (Not nuanced!) Idiomatic expressions are staged literally; the original word order and clauses of the Greek and Hebrew are preserved as close as possible. THIS TAKES A LOT OF STUDY IN LANGUAGE TO PERFORM! This is the Formal Equivalent. Such Bibles (in my view) would be the New American Standard, American Standard, English Standard Version, King James Version, New King James Version. (It should be noted these types of Bibles give the student and scholar an accurate idea of the wording of the original languages. Careful and detailed analysis of the text is the objective. That is not to say they are better; it is the purpose that is the concern.)

On the right side are versions that attempt to capture the ACCURATE meaning of the Greek and Hebrew, without truncating the syntax. These types of translations are little concerned with exact word-for-word phrases. However, they do pay special attention to the ‘style’ of English that is to be employed that is going to be used to demonstrate each particular verse. In theory, they do not want dangling elements of the original tongues of these verses ‘sloppily’ translated into English, which could infect the WHOLE translation with quite a distasteful fashion. This is what is called Dynamic Equivalence. Such Bibles included would be Contemporary English Version, Good News Bible, New Living Translation, and New Century Version.

In further demonstration, there are other Bible translations that fall in between both extremes. The most popular would be the New International Version. This version heroically advocates serving two master’s blissfully. One way being to preserve the original Greek and Hebrew syntax; the other way is to expand or invent a NEW English style of prose. The NIV has demonstrated this perfectly and is quite a popular translation among less conservative denominations. However, since this version does balance both extremes impeccably, it is an excellent translation for public reading and recitation. The New Revised Standard Version also performs a juggling act with Formal and Dynamic Equivalence. It is slightly more formal than the NIV but does retain a pleasant-sounding vocabulary to the reader. (Once again, however, it should be mentioned that most of these translations differ greatly among denominations and churches in general. Different groups of Christians differ on the TRUE content of the Bible. IT SHOULD ALSO BE REMEMBERED THAT THE BIBLE WAS NOT GIVEN TO US IN ENGLISH!) Roman Catholics and Eastern/Oriental Orthodox and Jehovah Witnesses use their own versions and scholars who provide the translations. For example, the Roman Catholic Church has never acknowledged the King James version of the Bible; they have used the Douay Rheims for a long time, and some Catholics still do; the Douay Rheims is an English translation of the Latin Vulgate that was done by members of the English College in Douai, France. Although the Eastern Orthodox Church now uses the New King James version for the New Testament, and a new translation of the Old Testament from the Septuagint (An ancient Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible) using the New King James version as a template with Orthodox commentary. Jehovah’s Witnesses use the New World Translation.

Here are some examples of Formal and Dynamic:

Formal

- He lifted up his eyes to Jesus

- Jesus said to him, saying

- And he opened his mouth, he taught them saying

Dynamic

- He looked at Jesus

- Jesus said to him

- He began to teach them. He said

The differences are in the taste of language and imagery. I should make the point that this is not an essay that is concerned with Textual Criticism or Hermeneutics, nor is this an emendation on the PROPER procedure of translation selection. I am attempting, however, to make the reader more aware of why the translations are structured in the mechanical and linguistic ways that they are. As I am reminded by Rabbi Shalom Bell, my old Hebrew teacher, when I asked him this question:

Me: “Rabbi, what is the best version of the Bible to read? Hebrew or English?”

Rabbie Bell: “The one that keeps you reading every day, Mark.”

Further Reading

Metzger, Bruce. The Bible in Translation: Ancient and English Versions. Grand Rapids, 2001.

McGrath, Alister. In the Beginning: The Story of the King James Bible and How It Changed a Nation, a Language, and a Culture. New York, 2001.

Bruce, F.F. History of the English Bible. Oxford, 1978.

Richards E. and O’Brien, Brandon. Misreading Scripture with Western Eyes: Removing Cultural Blinders to Better Understand the Bible. Downers Grove, 2012.

© 2024 – 2025, Mark Grago. All rights reserved.